Todd R. Forsgren

Artist Statement:

The World is Round

I'll be the first to admit that the seven parts of this photographic project are sprawling. These parts represent different threads in my studio practice that seeks, broadly, to understand how we come to terms with abstract ways of thinking about the landscape:

— Staring at the Sky and the Screen

— Dreaming of Other Celestial Bodies

— Wondering What They're Looking at

— Breaking Branches and Bending Grids

— Measuring Half-lives on the Horizon

— Traversing Lines on the Map

— Drawing Towards Significant Change

For much of human history, we’ve relied on the five senses to understand our surroundings. But these evolved senses can’t give us a complete picture, especially when confronted with ideas beyond direct observation, such as globalization. For these situations, we’ve come to rely on a combination of abstract thought and technology to grasp complex concepts. Using these tools, we can begin to understand a world beyond ourselves, and even learn how our senses can mislead (though the data from these tools can certainly be misused as well).

For example, based on direct observation the world seems flat, right? When philosophers and mathematicians first proposed the earth’s roundness, they were at odds with religious beliefs. But then astronomers noticed that this idea worked out very well with their calculations of planetary movements, and it started gathering momentum. Circumnavigating the globe provided a more direct proof. And finally, this could be observed most concretely through photographs of the earth from space. Yes, the world is round. And paradigm shifts like this one are vital to understanding our complicated planet. We need to learn how to "think globally."

Photography has been a critical tool in my quest to make sense of the world. And this series of images is a playful attempt to consider how photography and other imaging technologies, as well as photographic history, has been fundamental to such paradigm shifts. I've identified five overarching themes that I employ in this series to do so, and these themes help to organize this sprawling body of work.

These leaps in abstract thinking are often aided by new technological tools, and these technologies are becoming a more and more integral part of our daily lives. Yet reluctance to trust these abstract data persists, especially when the data are at odds with our sensory perception of the world. In the face of climate change and unprecedented globalization, we need to work to develop a deeper understanding of how technology can reveal hidden aspects of our planet.

These images are playful attempts to integrate nature and nurture. I hope that they act as riddles to reconsider perceptions and preconceptions about the global landscape. I seek to simultaneously hold contradictory ideas about the world and consider the divide between what is directly observable and the limits of what we can measure and comprehend. Photography is a central technology in this, and rather than focus on the current perceived divide between digital and film, I consider the history of photography as a continuously morphing and dynamic medium.

Taken from Wikipedia,

Political Ecology:

Political ecology is the study of the relationships between political, economic and social factors with environmental issues and changes. Political ecology differs from apolitical ecological studies by politicizing environmental issues and phenomena.

The academic discipline offers wide-ranging studies integrating ecological social sciences with political economy[1] in topics such as degradation and marginalization, environmental conflict, conservation and control, and environmental identities and social movements.[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_ecology

Todd R. Forsgren

Social Science,

Environmental Social Science

Political Ecology

The World is Round

I-Staring

Staring at the Sky and the Screen

The challenge of rendering three-dimensional space onto two-dimensional surfaces is a prehistoric one, as old as the petroglyphs that dot the earth. Photographic was a critical step to solving this: a precise mechanical means to copy the world, and it is becoming easier and easier to do every year. That has created a fascinating challenge: today, as our lives are mediated by smartphones and computers, we inhabit a world of man-made image almost as much, and in some cases likely even more, than the physical world. And now we must reconcile the two in new ways.

We continue to develop more and more technologies to make up for our body’s limits. These range from familiar tools such as cameras and microphones to specialized remote sensors made to record what is inaccessible to us, like detecting subatomic particles or the temperatures on the surface of the sun. Using statistics, experimentation, and intuition we can process this information and, hopefully, start to make sense of it.

Reconciling the information from my senses with what is recorded by new technologies and images is a challenge. But while doing so I’ve noticed a charged spaced between these two worlds, and in this space, is fertile ground to grow new ideas. Here, I try to make sense of a world that is now odd combination of direct observation/perception and what I’ve learned from experimentation and abstract reasoning. Figuring out which of these two approaches to trust is becoming increasingly challenging as I am presented with more and more points of view. What I rely on is a murky blend of information, intuition, knowledge, and skepticism.

288 Variations of a Cloudy Sky (Twenty-four Exposures at One Stop Intervals Printed with all Twelve Ilford Multigrade Filters), 2019.

Film: Rollei RPX 25

Lens: Leica Summilux 35mm

Camera: Leica M6

X-Axis: 1/1000 @ f/16, 1/1000 @ f/11, 1/1000 @ f/8, 1/1000 @ f/5.6, 1/1000 @ f/4, 1/1000 @ f/2.8, 1/1000 @ f/2, 1/1000 @ f/1.4, 1/500 @ f/1.4, 1/250 @ f/1.4, 1/125 @ f/1.4, 1/60 @ f/1.4, 1/30 @ f/1.4, 1/15 @ f/1.4, 1/8 @ f/1.4, 1/4 @ f/1.4, 1/2 @ f/1.4, 1" @ f/1.4, 2" @ f/1.4, 4" @ f/1.4, 8" @ f/1.4, 16" @ f/1.4, 32" @ f/1.4, 64" @ f/1.4

Y-Axis: 00, 0, 1/2, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5

Dark Skies: A Collection of 100 Makeshift Black Squares from Instagram’s #blackouttuesday, 2020

George Floyd was murdered by Derek Chauvin on May 25th, 2020. This event was a particularly grotesque example of long-standing violence and profiling that African Americans have experienced at the hands of the police and federal government in the United States of America throughout the nation’s history.

Exacerbated by the innumerable stresses caused by the coronavirus pandemic (which have disproportionately affected marginalized communities of color), protests and demonstrations erupted across the United States, and the world, at a scale not seen since the 1960’s. Many of these in person, but others in digital space.

One such event was on Tuesday June 2nd, 2020. #blackouttuesday flooded the social media platform Instagram. It was organized as a protest against the racism and inequality that people of color face every day. The simple gesture of posting a black square to Instagram quickly went viral, creating an endless scroll of black.

Most such images were “pure” black… squares with every pixel having a value of #000000. Others had subtle graphic elements in them, such as text like “black lives matter.” But this grid shows 100 “makeshift” black squares… Photographs that people took of empty-ish spaces and/or edited down to as dark as possible.

I found such images exceptionally beautiful, like the night sky: they contained subtle shades, gradients, and noise. Each one showing a unique and nuanced point-of-view. So, I collected them. The squares in this grid document 100 individuals’ struggles with their cameras in order to create a black photograph.

You see, cameras’ light meters try to make an exposure of 18% gray. Because of this, it is difficult to make a black photograph. So, if you listened to you light meter when photographing black skin, the resulting image would have a value much closer to white skin. Thus, to make a properly exposed image, you need to adjust the camera.

Seeing Spots: Macular Degeneration and Cataracts, 2012.

My father's father had macular degeneration and my mother's father had cataracts. They both served in the Pacific during WWII, and they both liked to be out on boats, they loved the open water of Lake Erie. Practical men, unlike their flighty arty grandson. I imagine them, staring intently at the horizon, as their decaying eyes began to obscure the view. I imagine one, then I imagine the other, as I gaze out at the great lake that they both loved so dearly.

II-Dreaming

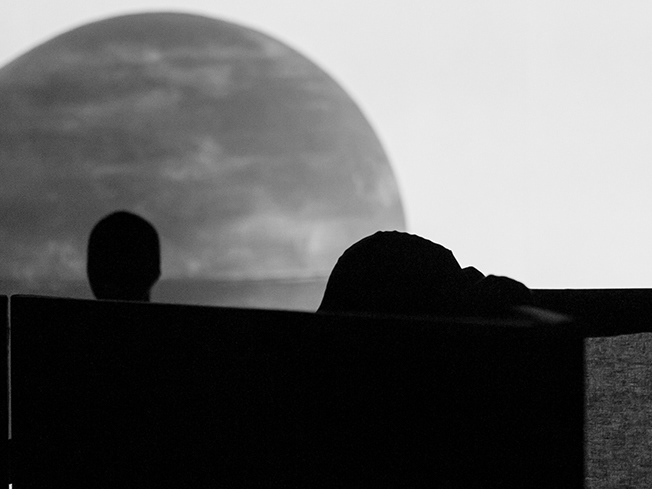

Don't Trust What You See Here

One morning I was gardening in New England when my friend Toby stopped by on his way to work. He was restoring the local church’s steeple and he asked me if I’d like to see the work he was doing… Interested, I went inside to put my contact lenses in, and forgot I had just been handling some very very hot peppers. We then jumped into Toby’s convertible and sped off to the church, the crisp air digging deep into my already inflamed eyeballs.

Following the climb up the 200-foot steeple’s maze like interior, full of dust and 150 years of pigeon shit, my eyes were streaming tears. I got to the top and peered out the small window, but I couldn’t see the beautiful vista, because my eyes could barely open.

On another morning years later, as I was waking up in a hotel in the Caribbean, I noticed that I was paralyzed. I could see the room around me and hear my friend Marc snoring in the next bed, but I couldn’t move my body. Instead I saw a pitch-black figure, an incubus, standing above me. It was the first time I dealt with sleep paralysis, though I’ve experienced it several times since… Sometime the figure that visits me is frightening, other times it is calming. Scientists can offer convincing reasons for this phenomenon and the accompanying hallucinations: only parts of my brain wake up, while others remain in a dreaming state.

These are two instances when my body and my brain failed me (though I’m blessed to be a relatively healthy person). These failures, however, were profound experiences. Because these moments are when I felt my physical and psychological limits most acutely and I understood so clearly that there is much in this world that I can make sense or understand. I’ve grown more comfortable within this space sense, and I found failure to be a fruitful place to make art.

This is Not an Event Horizon, 2012.

Every night the stars all seem to revolve around the North Star, Polaris. This isn’t what’s really happening, of course. The effect is actually caused by the earth’s rotation, but it took us humans a long time to figure that out. I’d bet that every night, someone out there somewhere is photographing it. Making star trails. One night that person was me. It is certainly miraculous, but sometimes it also seems like a broken record that is stuck on the same song. This picture is my reflection on our attempts to rediscover known miracles.

Stars, Moons, and Planets (Nine Salami Photograms), 2019.

On a hot summer evening, sitting outside at a social event, I found myself stuck between two folks I was struggling to connect with and a big board of charcuterie in front of me.

As I picked up the slivers of meat and the setting sun glinted through them, I couldn’t help but think how similar some were in both tone and opacity to color negative film.

So, I went to Whole Foods Market and bought a range of salami and other circular meats sliced at a variety of thicknesses, and I took them into the darkroom to make these photograms. Pressing the meat directly against the photo paper, mixing the cyan, magenta, and yellow filters, I tried to create stars and moons and planets out of them, while thinking of the pigs.

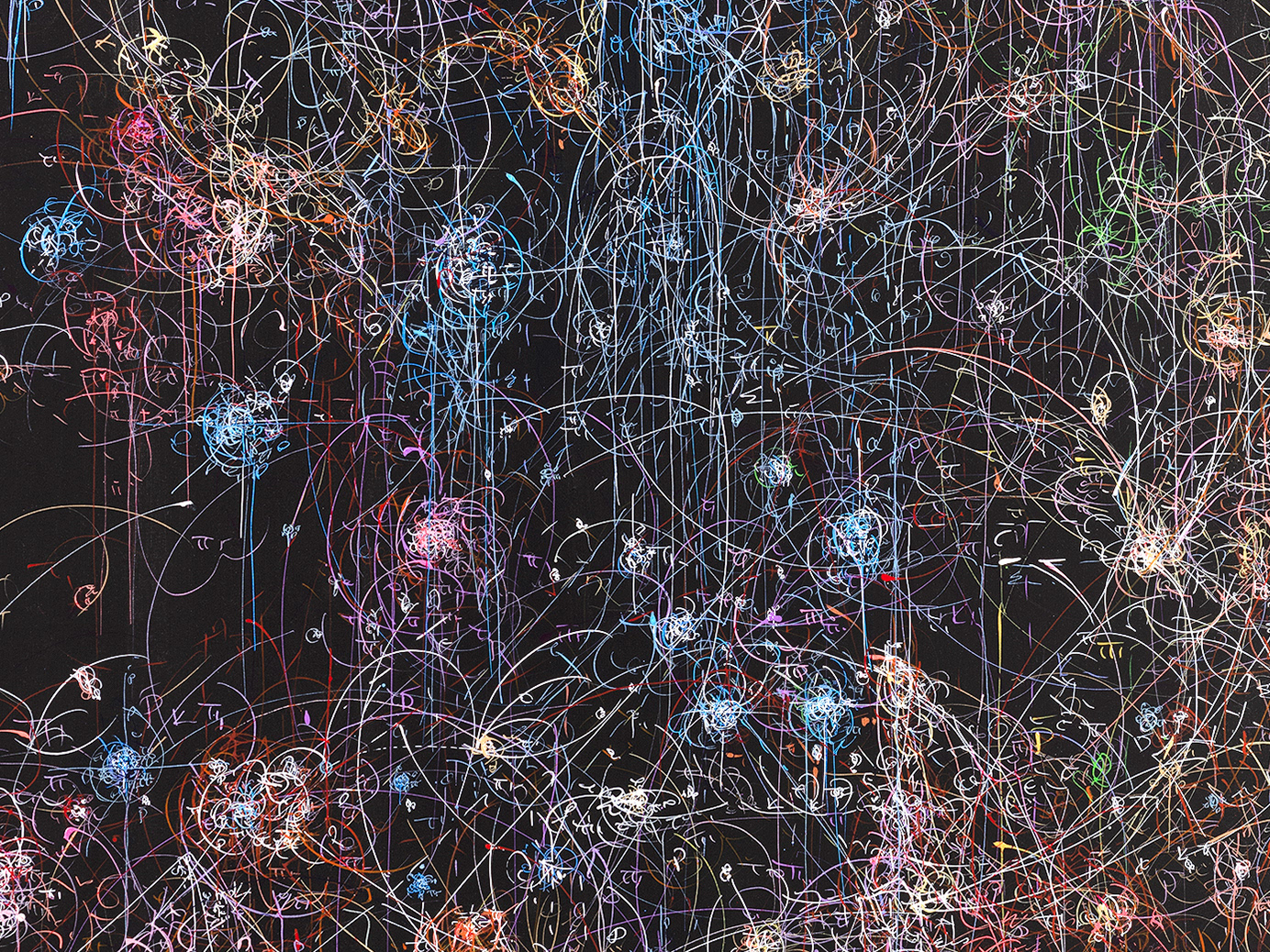

Supernovas from Mix CDs:

Documentation of the Obliteration of Information, silver gelatin prints, 2016.

In the late 20th Century and early 21st century, there was rapid technological innovation and change. The world-wide web happened, for example. During this period, I also happened to come of age. Growing up, two technologies held a special symbolic value, offering the promise of better living through innovation. The Compact Disc and the microwave. Today, both these technologies feel dated, like something from my childhood. Which, I guess, they are.

The CD was born just one year after me, in 1982. It reshaped the audio, video, and data storage industries. These spinning disks contain a long coil of information which can read by an optical drive and 780nm light, (close to infrared in wavelength, on the far edge of visible light). I used to love “burning” disks, making my own personal music mixes or a mix for someone special to me often as a romantic gesture.

In the 1980s, the microwave oven was rapidly becoming a common household appliance. I remember when my family finally got one; it seemed like magic. These ovens allow for the rapid heading of food using the vibrations caused by microwaves, an invisible wavelength on the electromagnetic spectrum between 1mm and 1mm (on the other side of infrared light compared to what CDs use).

The wavelengths used by these two techs are rarely used in my favorite technology, photography. But I wanted to make photographs of them. And I remembered: put a CD in a microwave, turn on the microwave, and boom, the CD explodes creating visible light. I found those old CDs that I’d burnt or had been burnt for me… and I put them in a microwave oven, on silver gelatin photographic paper, to record the end of that era.

Supernovas from Mix CDs:

Documentation of the Obliteration of Information, silver gelatin prints, 2016.

In the late 20th Century and early 21st century, there was rapid technological innovation and change. The world-wide web happened, for example. During this period, I also happened to come of age. Growing up, two technologies held a special symbolic value, offering the promise of better living through innovation. The Compact Disc and the microwave. Today, both these technologies feel dated, like something from my childhood. Which, I guess, they are.

The CD was born just one year after me, in 1982. It reshaped the audio, video, and data storage industries. These spinning disks contain a long coil of information which can read by an optical drive and 780nm light, (close to infrared in wavelength, on the far edge of visible light). I used to love “burning” disks, making my own personal music mixes or a mix for someone special to me often as a romantic gesture.

In the 1980s, the microwave oven was rapidly becoming a common household appliance. I remember when my family finally got one; it seemed like magic. These ovens allow for the rapid heading of food using the vibrations caused by microwaves, an invisible wavelength on the electromagnetic spectrum between 1mm and 1mm (on the other side of infrared light compared to what CDs use).

The wavelengths used by these two techs are rarely used in my favorite technology, photography. But I wanted to make photographs of them. And I remembered: put a CD in a microwave, turn on the microwave, and boom, the CD explodes creating visible light. I found those old CDs that I’d burnt or had been burnt for me… and I put them in a microwave oven, on silver gelatin photographic paper, to record the end of that era.

Another Route to the Moon

I met Jeff years ago, while I was hitchhiking in Australia. We drove from one end of it to the other through a large desert where we watched thunderstorms roll along the horizon. Two days later, flowers bloomed everywhere.

Years before we met, Jeff was deep in the jungle on another island. It was the 20th of July in 1969 when he heard over the shortwave radio that Apollo 11 had brought a man to the moon. At the time, he was living with a remote tribe of people who had had little contact with the wider world. That night, around the campfire, he mentioned the moon landing to one of the shamans in the village…

As I remember the story, which Jeff told me one night around a camp fire, the man smiled at him and asked calmly, “Did he stay long?”

“Umm… No,” Jeff responded.

“It’s very hard to breathe up there,” the shaman replied, knowingly sifting a bit of ash from the campfire through his fingers, “and it’s very dusty.” Unimpressed by this feat of Western technological achievement, the shaman went on to explain that he traveled to the moon on a regular basis via other means.

I’m not certain if Jeff’s shaman friend still travels there by these other means. But I am fascinated by the idea of this other route to the moon. Often, there are an infinite variety of routes to the same goal, and I hope to explore these less traveled routes. By doing so, I hope to squeeze a bit more interest out of even the most tired tropes of image making.

Orb, 2018.

In the haze of jetlag, I saw this strange orb floating amongst the birch trees above the path to nowhere.

Lunar Landscape, paired 4"x5" ambrotypes, 2013.

In a world where dry photographic emulsion wasn’t invented, man would’ve had to continue to use wet-plate photographic techniques. I imagined this world, and what would our pictures of the missions to the moon would look like… A wet-plate version of Earthrise, for example. Although it'd be very hard to pour collodion without gravity’s help.

Trying Not to Go Blind, inkjet print with cigarette burn, 2017.

One evening I was jogging along the Caribbean Sea in southwestern Puerto Rico. I came upon a little bluff overlooking a small secluded little beach, less than 100 meters long. There was a man standing in the middle of that beach, looking out at the sunset. And he was masturbating. At first I thought that this was pretty twisted, but as I reflected on it on my jog back home, I began to see a beautiful poetry to his Quixotic quest. Although he was certainly playing with fire, because both these things can make you go blind.

III- Wondering

Wondering What They're Looking at

Empathizing and understanding other points of view is crucial in today’s multicultural and politically polarized world. It has made my image world richer, to understand these diverse culturally histories, and to be able to play with this when I make art. This understanding of human culture and its myriad of differences is critical.

But in this fractured world full of new types of tribes, understanding universals seems daunting. The modernist sought universality in the square, and while it’s important it seems too cold. I seek this connection by trying to leap back and forth between these analytic and intellectualized ideas and that of my animal brain and our shared and primal evolutionary history.

44% blue and 555 nanometers. I find these two values fascinating, because they point towards a connection in our humanity. 44% of people in America say blue is their favorite color. And human eyes are most sensitive to colors with a wavelength of 555 nanometers. These seemingly precise values point to our deep evolutionary history, that lost and forgotten common ancestor, the missing link.

In my opinion, a deep consideration of our evolutionary biology has been largely overlooked or even intentionally ignored by critical theory and popular approaches to art making over the past century. In the sciences, this played out in the “nature vs. nurture” debate (nature being our genetic information and nurture being cultural knowledge). The conclusion that biologists came to is that it impossible to separate the two, nature AND nurture are critical. We need our rational side and our emotional side. The trick is how to reconcile the two.

Tankman from Five Perspectives, 2016.

Jeff Widener was staying on the sixth floor of the Beijing Hotel in 1989, overlooking Tiananmen Square. He was 800-meters away, on his balcony, from where a man stood fast in front of a column of tanks. It culminated just as he was running out of film, but then his friend Kirk handed him another roll of Fuji.

Stuart Franklin was on another balcony in the same hotel, pointing his camera at the scene below, his lens not quite as telephoto. In his picture, we see other details… Tiananmen Square looks like a pleasant public space. To smuggle his film out, he gave it to a French student. The photo left China hidden in a box of tea.

Charlie Cole was next to Stuart Franklin and he hid his film in the toilet of the Beijing Hotel. He sacrificed two other rolls of film to the Chinese Public Security Bureau when they raided his hotel room looking for it. One contained images of protests that he had been beaten during and the other was blank. Did the PSB develop them?

Arthur Tsang Hin Wah was on another balcony at the Beijing Hotel. He had been beaten up the day before, and the PSB wouldn’t let him leave his room so he was stuck. So, his photo is from Room 1111. The day before, a photojournalists friend of his left China, telling him, "I am not gonna die for your country."

Terril Jones was the only photojournalist on ground level, hiding behind a rack of bicycles. We see the faces of two protestors running away. Jones’s photo is not from that seemingly omnipotent vantage point of an ‘eye in the sky.’ It was taken 20 second before the others, but didn’t surface until 20 years later, in 2009.

Constant Surveillance 001: My Studio and My Daughter's Nursery, lumen Print exposed from October 2016-April 2017.*

Photography had a triple birth in the mid-1800s: One in France, one in England, and a third in Brazil. All three of the “first” images are of landscapes framed by architecture. The reason was largely practical: exposures took a long time in those days and landscapes will hold still for the required hours. And the images were taken out of the author’s studio windows so that they could be close to their chemistry sets.

When my daughter was born, my studio became her nursery. One evening, I was looking out the latticed windows of her room as I rocked her back and forth trying to get her to sleep, reflecting on all the firsts we had been experiencing together. And reflecting on this history of the first photographs.

My daughter and her generation will likely live hyper-photographed lives just 200 years after those first photographs. Rather than install a baby monitor to watch her, and my studio, I placed a pinhole camera on the wall. An unobtrusive frame to capture every moment but simultaneously no moments. So now while our lives change so quickly, we also have a reminder that is rooted in a much slower pace of discovery. My first try was this six months long and the image was still under exposed. The next will be at least a year, I think.

* By the way, this series is ongoing. If you’d like to rent the camera for six months to a year so I can take a photograph of your home or office space, please contact me.

Constant Surveillance 002: Every Hour of the Rotterdam Photography Festival, 2018.

In February 2018, I participated in the Rotterdam Photography Festival (https://www.rotterdamphotofestival.com/exhibitionprogram).

During the week of the festival, I set up a pinhole camera to take photographs with hour long exposures using Fuji FP-100C film. The images are of the same subject: the exhibition space and entrance, and the result is a record of every hour of the festival. This work was part of an exhibition Camera Works that included two other artists: Marc Redford and Michael N. Meyer (http://www.michaelmeyerphoto.com/).

Here’s an excerpt from John A. Tyson’s text about the exhibition: “Todd Forsgren’s Constant Surveillance (ongoing) collapses the technology of nascent photography and our image-saturated present. With pinhole cameras he records spans of hours or even years, catching every moment and no single moment simultaneously. Although the project evokes panoptic disciplinary technology, its images are decidedly more aesthetic. Installed in Rotterdam, his work will create an expanding archive of contact prints throughout the festival. Unlike the standard, time-stamped surveillance images, Forsgren’s photos resist bearing the trace of a singular moment in regimented clock time. Nonetheless, their literal, indexical linking his analogue feed to its surrounds is important too. Recalling the tautological logic of Robert Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (1961) (a cubic wooden sculpture with a recording inside), the temporality of exhibition becomes coextensive with that of image production in Forsgren’s poetic surveillance.”

View of Fuji on Kodak on Fuji, 2009-2011.

Sometimes I like to make photographs that are as convoluted as possible. For example, here’s a fictional Mount Fuji in a rainstorm with a color space rainbow. I made it out of cut up photographs of Mount Fuji and rainbows and clouds. Then photographed on Kodak Portra 4"x5" 160NC. I wet mounted the negative to scan it at 4800dpi with an Epson V750 scanner. Then added Adobe Photoshop CS5 histogram sliders and printed it on Fuji Crystal Archive paper at 8"x10", mounted on aluminum with a plexi facemount.

The Most Primal Landscape (44% blue over 555nm), 2017.

555 nanometers and 44% blue. These two numbers represent, to me, the complicated relationship between our biology and our culture. Nature and nurture, if you will. In an Artworld that is often driven by cultural context, they’re an expression of our inability to escape this biology. Such precise values, however, seem oddly analytic given this primal and prehistoric nature. And so, I used these to colors, one as land and one as sky, to create the most minimal landscape I could think of, and perhaps the least photographic image I’ve made in years.

Human eyes are most sensitive to light with a wavelength of around 555 nanometers. A fresh shade of green close to the color of new plant growth. Perhaps it’s so that our ancestors could locate nice fresh growth to eat during hunter-gatherer times. Or maybe it even developed during human’s long history with agriculture, as our ancestors tried to assess the health of the crops they were growing. It’s impossible to know exactly why; we can’t use the scientific method on prehistory, so it’s all just guessing and storytelling.

With remarkable global conservation, across countries and cultures (as per Komar and Melamid’s surveys in the early 1990s), blue is the most popular color. Conducted for the sake of conceptual art, this is the only scientific survey on this subject that I could find. I extrapolated from their survey in America, where 44% of the population’s favorite color is blue. To absurdly imagine this color as a precise shade, based on the mixing of RGB color channels, I also included the runner’s-up for favorite color: 12% green and 11% red.

What do You Want? And Why?

In the 1990’s, Vitaly Komar and Alex Melamid conducted extensive surveys on preferences in art in eleven countries as part of their Most and Least Wanted Painting series (one of my favorite results from this survey is to know that globally, blue is by far the most popular color. In the U.S.A., for example, 44% of respondents identified blue as their favorite). Komar and Melamid used this data in their suite of tongue-and-cheek “most wanted” paintings.

Through those surveys, they discovered an interest in a “mostly blue landscape with trees, water, mountains, and humans and animals.” They made paintings that showed this landscape, which were just as primordial as they were kitschy. This provocation has led to diverse discourse in the arts, with a range of theories attempting to explain why such a similar landscape is persistently popular across cultures. Arthur Danto and Denis Dutton came up with very different a priori reasons to justify this nearly universal trend.

Arthur Danto, famous for coining the term “The Artworld,” reasoned that the popularity of this landscape was due to, essentially, nurture. Danto wrote that the first art seen by so many people in countries across the planet are calendars, desktop images, kitschy grandmother paintings, and postcards of pleasant sunsets and beautiful landscapes. Thus, his argument goes, these are the images most people first associate with art unless they have another and more profound art experience to replace it.

Dennis Dutton, on the other hand, argued that the reason has more to do with our evolutionary biology: these landscapes are like the ones that allowed our ancestors to survive. Their fecundity is what attracts us, and why artists in many cultures have made images of this type of a landscape, often independent of one another. The global popularity of these landscapes on calendars and postcards is a result of this evolutionary history, not the cause.

Separating the chicken from the egg in this way is very tricky business. In my photographs, I attempt to reconcile nature and nurture, rather than try to separate the art historical context from our biological connection. So even as our technological tools develop and our Artworld embraces the difficult to access avant garde, we are and always will be deeply connected by our biological roots. Understanding these roots is as critical to my approach to artmaking, because if we are to find anything that will connect us, I believe it will be in the depths of our shared natural history.

Four Blank Landscapes, 2016.

Interesting things often happen in unremarkable places. In these photographs, something interesting happened but that event has been removed. So all we’re left with is the place and a shadow of that memory.

IV-Breaking

Break Branches and Bending Grids

The sciences and the arts often use very different approaches to abstraction. In the sciences, for example, abstraction tends to be data driven: how can numbers show us something new about the world? In the arts, it is most famously thought of as the opposite: how can abstraction reveal expression? This divide persists in many people’s perception of the two fields: art is expressive and science is analytic. But I think of a camera as a machine that both measures and expresses. And I think of art and science as compliments.

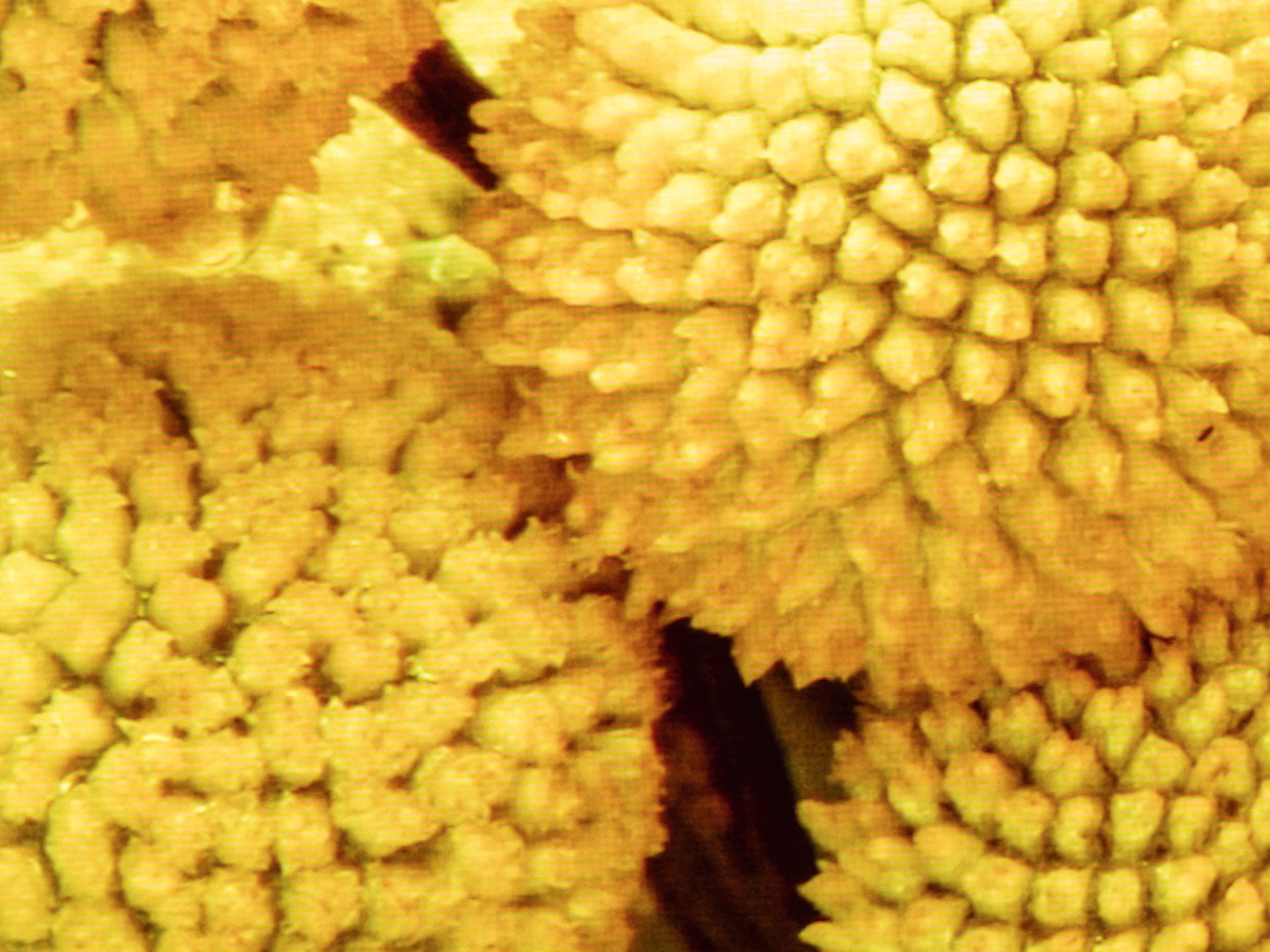

Grids and branches represent two very different systems for interpreting and reproducing the world. They’re the underlying data of today’s image files: pixels or vectors. Both systems are incredibly useful, and which to use depends on context. Vectors are horrible at carrying photographic information. Grids (or the crystalline structure of film grain) are essential to it, but that information breaks down when magnified. But using the various systems we’ve developed to see the world together, we can find new insights and surprising images. Moiré can result in the positive and negative reinforcement of different sized grids. Branches start to entwine as vines grow together, creating knots that seem impossible to untie. Other times, these layers show the cracks in each system.

I often find one things breaks, something new begins to present itself. And I find new ideas that are hidden in the world. In ecology, for example, loose trends often leave us with scatter, and only through complicated mathematics can we map these vague trends at the abstract and penumbral edges of the world. By breaking these systems and trying to put them back together in unusual ways, I try to glimpse at the imperfect, unusual, and broken edges that are created: the remaining wildernesses.

A Study of Perspective (Above, Level, and Below), 2017.

Diameter at breast height (DBH) is a standardized measurement that is used to express how large trees are as well as how dense a forest is. It’s straightforward: just take a measurement of the diameter of a tree at breast height (which is 1.3m high, by the way). But it’s controversial: despite this standard, many scientist argue the value has problematic biases. If you believe in DBH, you can measure all the trees within a given area and from these data calculate biomass of the forest. This is a hard thing to measure accurately: there are so many variables at play!

One of the tricky things about ecology is that the data we get is often very subtle and there are so many variables at play. In photography, I often call skittish ideas like this ‘penumbral.’ From one angle I can see something, but from another it’s chaos. We can best understand some concepts through statistics, which allow us to line up data about the world in a way that we can’t directly observe. To demonstrate this, I tied pink ribbons around all the trees in a forest at their DBH. I took one photograph from 0.5m above DBH, one at DBH, and one from 0.5m below DBH.

Testing the Symmetry of a Landscape, 2016.

While paddling upstream I found a circle of water lilies in the river that seemed too perfect to be true. With a diameter of about 100 feet, it was a mystery to me. What had created it? I decided to test this circle, to see if it was repeatable. I photographed it as precisely as I possibly could from my perch on the paddle board. Later that day on my computer, I mirrored it to the left and to the right. Like the father and the son and the holy spirit, each of the ensōs look unbelieve. But one is real, I swear, it's god's honest truth.

Forest Fragmented by 64 Exposures, 2013.

The world's forests are getting chopped up into smaller and smaller bits of land. This is what ecologists call forest fragmentation, and it’s really bad for ecosystems. So, keeping the horizon straight, I moved my camera in a circle, spinning it for 64 exposures and further fragmenting the small patch of forest.

18% Grey Cave with Digital Stalactites and Stalagmites, 2017.

In the movie The Matrix, the virtual computer world looks like green zeroes and ones falling across the computer screen. I saw a glimpse of that world when someone sent me this photograph of my daughter and it got clipped by an e-mail server somewhere in between.

A Tree for Mondrian, Rorschach, Techentin, and Zimmerman, 2016.

I like order. I like different types of order. There are grids and branching patterns and symmetry. Some people use order to make art. Some use order to make science. Here, I tried to use order to make more order, and see what would happen if I tried to fit all these types of order into one image.

V-Measuring

Measuring Half-lives on the Horizon

“But I always found myself returning to the outside and always found myself wanting to see more and more space, to be able to orchestrate larger and larger volumes of space.”

Frank Gohlke said that. I admire his ambition, but also find something troubling and strange about this idea of controlling such a big part of the landscape. It scares me that I crave this too. To capture big chunks of the world in my little camera.

Left and right. Right and wrong. These simple dichotomies we use to think about the world are tied to our biology and our bilateral symmetry. We categorize the world breaks it down into oversimplified chunks that we can digest. We need them because we can’t grasp the bigness of the horizon. So we’re stuck, between the imperfect breakdown of the world in order to understand it and the aspiration to experience it all.

Oftentimes these simple systems work so well: night and day. Every day the sun rises and the sun sets. But there are several very rare natural phenomena that some people spend years and lifetimes looking for, even chasing. The green flash, flash spectrum, lunar eclipses, solar eclipses, the northern lights, and the Brocken spectre, to name a few. These events are much rarer than rainbows, in part because it requires specific planetary alignments as well as ideal atmospheric conditions to observe them properly. They create a paradox for me that’ I’ve been trying to recreate in my photographs. Because somehow, in these moments I feel connected to the world’s bigness at the same time I understand the concepts that cause them to occur.

Prime Integer Topology: A Mountain from the Sea by Multiple Exposures (in the Darkroom),

Using 1 and Increasing Primes 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, & 67, 2018

Four Seasons from Green to Pink and Positive to Negative, 2018.

This grid of photographs shows a gradient from four corners of opposing versions of the same scene:

Upper Left: A positive image on Kodak Portra 160.

Lower Left: A negative of that Kodak Portra image.

Upper Right: A positive on Kodak Aerochrome.

Lower Right: A negative of the Aerochrome image.

Afterwards Comes Oblivion, 2015.

John McKee first showed me Walker Evan's photographs. We looked carefully at one landscape: Rocks, scrub, and bushes with a lone tree on the horizon. John talked about it in his soft and understated way, “consider the difference between looking and seeing.” John was always searched for the bones of the landscape, and this image showed those bones. We talked about the architecture that held the photograph together. It was subtle, John explained, “Easy to break.” So I scanned and printed it, and scanned the print, over and over again. The landscape faded, the tree became a mushroom cloud. It was abstracted more and more, until I’d squeezed everything out of the picture and there was nothing left.

Discovering Icebergs with my Daughter, 2016.

In January 2016, a record breaking blizzard hit the Mid-Atlantic. By late February, the snow had finally melted, well, mostly... It had melted enough so that I could push my six-month old daughter in her stroller. We went for a long walk through the neighborhood.

All that was left of that record breaking blizzard were a few dirty and melting piles of snow, left where plows had violently pushed it. It was piled up in the margins and pushed aside into the corners, little icebergs on the edge of the landscape.

As we walked, I reflected on these little icebergs and on this world that I had brought my darling daughter into... The dirty snow looked amazingly beautiful and complicated. I began to wonder what icebergs would remain for her to see.

Rose Window, 2015.

In collaboration with Matthew Moore. This piece consists of a curated selection of over 1000 slides from a college art department's slide library.

Seventeen Failed Attempts at Photographing Lightning, and Four Partial Success, 2017.

During the most incredible lightning storm I ever saw I was armed with only my iPhone. Plus, I was in a bit of a rush to get inside and out of the rain. So, I quickly pointed my iPhone up and took twenty short snaps, hoping to catch one of the amazing bolts of lightning branching across the sky. Most of these photos were complete failures. But you can see a bit of lightning in the corner of one of them, and the sky illuminated from flashes off frame in two others. Somewhere, in the space between these twenty pictures, the lightning flashed in front of my camera, and it was glorious.

My Body Projected Over the City

On a mountaintop, just south of Ulaanbaatar in November of 2008, I saw my shadow projected over the city, surrounded by a rainbow-colored halo. It’s a rare phenomenon call a Brocken spectre.

This was the day before I left the Mongolia, after almost a year in the country. Down in the city the air was full of the dense pollution that hangs above Ulaanbaatar for the cold months. It’s a valley where 1.5 million people live, and are trying to stay warm as temperatures regularly reach -40° (the only temperature where Fahrenheit and Celsius are the same) by burning coal and wood and dung. But there is a clear line on that mountain, an elevation where the smog stops; so I was standing above the pollution, in fresh mountain air.

The sun was setting behind me, and the mountain’s shadow was looming over Ulaanbaatar. Just as I was about to step back down into that layer of smog, the Brocken spectre appeared for just a moment… my shadow seemed to be cast over the city, larger than the mountain. There I was, huge and surrounded by a halo shaped rainbow. Divine? The whole event lasted no longer than a few seconds. By the time, I thought to pull my camera up in front of my face, the vision was gone. But for one moment I felt like I was part of this amazing planetary alignment. I felt enormous.

The world is a very very large place compared to any one man, but there are billions of us. Humanity’s ability to impact and change the planet and its ecosystems is undeniable. It’s for this reason that scientists are not referring to the world today as “modern” or “post-modern” or “post-post-modern” or “contemporary”; instead the consensus is that we have entered a new geographic epoch that they refer to as the Anthropocene. For our effect is great on this planet.

VI-Traversing

Discovering Peary Land: A Photographic Survey of Northern Greenland, 2016-18.

An ice sheet covers 80% of world’s largest island, blanketing it in white. Despite this stark landscape, Eric the Red called the island “Greenland” when he landed there over 1000-years-ago. It’s widely believed that the name was an attempt at marketing; trying to encourage Viking settlers to join him (although the region’s climate was a bit warmer back then too). These settlements were likely never larger than 2500 people and were abandoned in the 15th century. Although the Vikings left, the name stuck.

Today, Greenland, an autonomous constituent country of Denmark, is the least densely populated territory in the world. Almost 90% of its 60,000 residents are Greenlandic Inuit, residing primarily along the southeastern coast of the country. The vast majority of the island is uninhabited by humans.

On the far northeastern tip of Greenland is an extremely remote region called Peary Land. There are no permanent settlements on this 57,000 km2 of, although the remains of prehistoric villages have been found (dating from c. 2400-200 BCE) and it is home to two scientific research stations (among the farthest north outposts in the world).

The landscape consists of polar deserts and glaciated mountains cut by deep Arctic fjords.

Sparse vegetation sustains caribou, musk ox, Arctic hare, and lemmings. These, in turn, sustain Arctic fox, polar wolf, and polar bears. Colonies of seabirds, gulls, and geese dot the region in the summer, flying south to avoid the long and dark Arctic winters. This remote arctic region is far from untouched by man. The delicate Arctic ecosystem is extremely vulnerable to climate change.

This book is a photographic exploration of Peary Land, considering the different ways this land has been touched by humans. I have never visited Peary Land, so my exploration relies on appropriated images. To understand this remote landscape, I have used three sources which, like the Greenland’s name, are all interestingly misleading or incomplete.

Traversing Lines on a Map

I. Like photography, mapping has gone through several technological sea changes in my lifetime: GPS, GIS, smartphones, TripTiks, MapQuest, Google Maps and Street View. These changes extend beyond literal maps and into the way we navigate information and ideas.

Such technologies have also altered how our brain functions and is structured.

I’ve almost always thought of image making as trying to figure out interesting ways to get from point A to point B. Perhaps it is my analytic training: the scientific method that I spent so much time thinking about and applying during my most formative years (incidentally, years when mapping and photographic technology were both changing rapidly). In the scientific method, one progresses from a question to research to a hypothesis then an experiment to analysis of data to a conclusion followed by reporting the results. Normally, this leads to ever more questions in an ever-expanding field of knowledge.

This path of the scientific method still matches my artistic process as much as any schematic I’ve encountered. There are other lines superimposed onto how I map my approach photography, those lines that help me decide what question to ask or how to construct my photographic ‘experiments.’

II. In her 1979 essay Sculpture in the Expanded Field, Rosalind Krauss lays out how several transects create a framework for new practices in sculpture during the Post-War upending of the medium. Her result is a square within a diamond, denoting interlocking pseudo-opposites which one can use to map these new approaches to sculpture, and how sculpture was pushing beyond its traditional frame: site-constructed—sculpture, marked sites—axiomatic structures, landscape—not-landscape, architecture—not-architecture, (complex—neuter).

In 2005, her former student George Baker tried to do something similar in his text, Photography’s Expanded Field. Closely mirroring Krauss’s approach while considering photography in the digital transition: “still film” projected images—“film still” cinematic images, digital montage “talking picture”—modernist photography, narrative—non-narrative, stasis—non-stasis, (complex—neuter).

There are plenty of other “maps” of critical issues in photography beyond Baker’s. Perhaps the most persistent vernacular framework, somewhat miraculously to me, is the analog—digital divide (throughout my career it has persisted as the first question most people ask about when they hear I make photographs; I happen to use both, often quite blended together). The second question has often been, are you a Canon or a Nikon person (i'm neither).

Barthes wrote of studium and punctum. Szarkowski’s came up with five fundamental principles: The Thing Itself, Vantage Point, the Detail, Time, and the Frame. Vilém Flusser grounds his Towards a Philosophy of Photography on the idea that “two fundamental turning points can be observed in human culture since its inception,” “linear writing” and “the technical image.” But like Krauss and Baker, my map is made of interlocking opposites: expressive—analytic, abstract—representational, past—future, specific—general, (observation—experimentation).

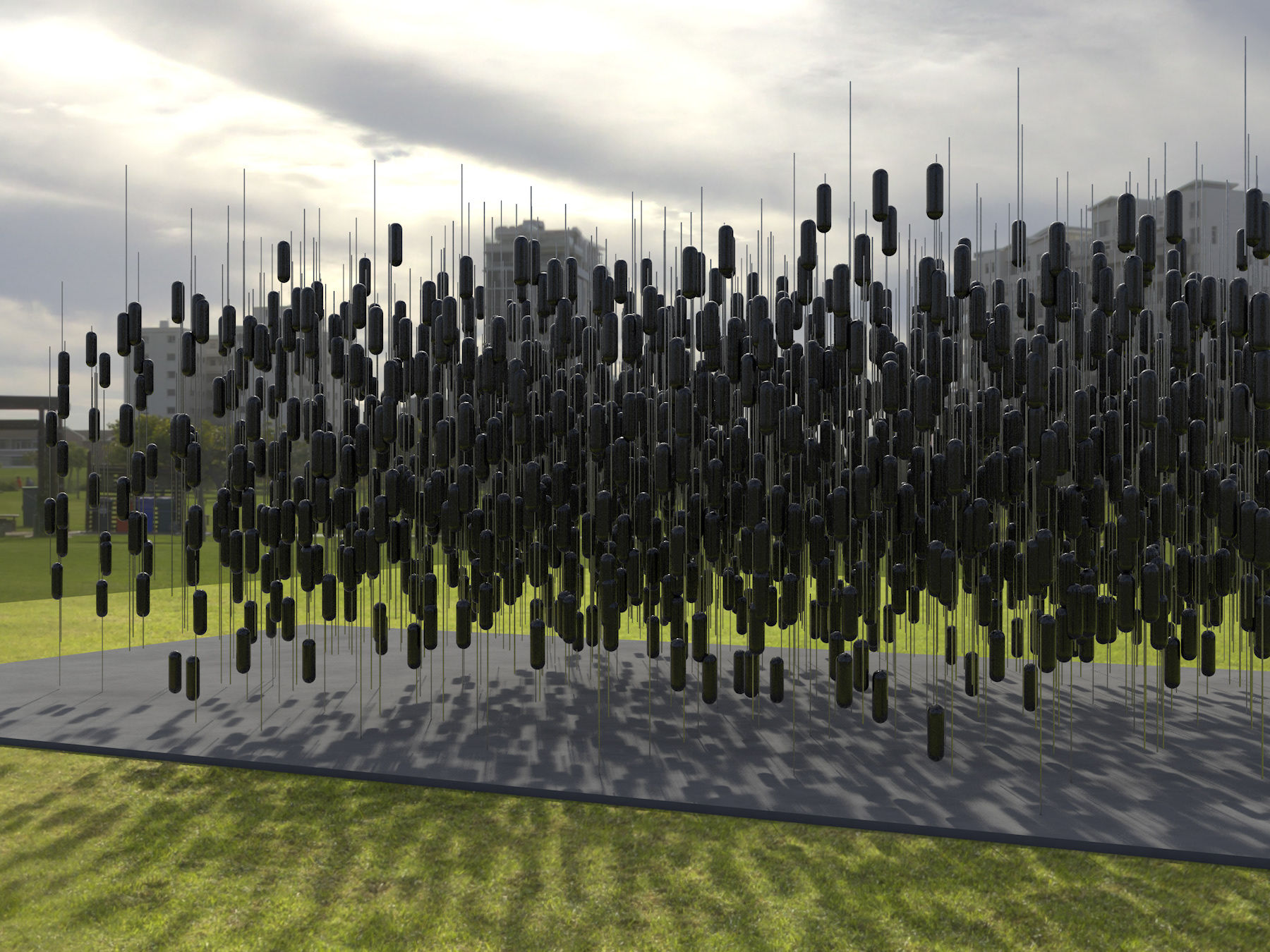

Bayer Filter Array Garden, acrylic panels on grass or moss, 2014.

Last summer Mika dreamt of a red and green and blue fence. She saw it extending across a wide river. It was lumpy and formless in an impossible way. At the time, she was also researching Carl Andre and the Japanese garden at Tofuku-ji, and our conversation shifted from her dream and to her research. I remember when I first saw the grid of Tofuku-ji‘s west garden, when I was an undergraduate in Intro to East Asian Art, with Professor Clifton Olds. The garden consists of a grid of billowing bright green moss and hard edged granite squares. It was designed by Mirei Shigemori in 1939, when Carl Andre was just four-years-old.

Suddenly, in my mind’s eye, these images collided. I saw a Bayer color array filter covering the earth. This mosaic of red, green and blue that is used in billions of digital cameras was extending in every direction. This pattern has been used to take trillions of digital photographs. Each square gathers data for just one color channel: red, green, or blue. Algorithms fill in the other two channels based on values from neighboring pixels, creating full color images. These intricate algorithms normally work quite well, but sometimes the data is unclear the camera starts to guess. The result of this is what we call digital “noise.”

Bayer Color Filter Array Garden is a huge physical version of this pattern. Though quite clear to the human eye, the edges between colors can start to confuse a camera, it begins to see noise caused by the quick change in color. The image breaks down more and more as the size of the squares of the grid approach the size of a camera’s pixels. In this case, each of my sculpture’s squares are about 1/4 the size of a pixel of resolution in USGS satellite maps. So my garden will confuse the hell out of those satellites, as they try to peer down into our lives.

Every Makeshift Home on Skid Row (that could be found on Google Street View on August 22nd, 2018), 2018.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s and William Henry Fox Talbot’s first photographic images are pictures of architecture fading into the landscape. They created views out their studio windows, but the photographs are literally disappearing due to instability in the material used to depict them. Even as the technologies have improved, this theme has continued to fascinate photographers, persisting from pictorialism and modernism to conceptualism and post-modernism.

Eugène Atget spent thirty years (1897-1927) documenting the Paris he loved as it disappeared into modernism. His goal for this “Old Paris” collection was to document everything… From the grand architecture along the Seine and everyday street scenes to the poor and homeless in the periphery of the city. His images received critical acclaim only after his death.

Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange (as well as many other American photographers in the late 1930s and early 1940s) documented the impoverished homes and lives of those affected by the Great Depression. They were employed by the United States Government through the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and were working at the direction of Roy E. Stryker. The FSA was a stimulus program used to combat the very poverty that the photographers where documenting.

Bernd and Hilla Becher spent 50 years documenting Germany’s disappearing industrial architecture. They arranged their precise and deadpan images into typologies, grids of structures that had similar function. By photographing these buildings, they created hyper-aestheticized images that considered the form of incredibly functional architecture.

In the turmoil of Post-War Japan, an accordion book called Album Ginza Haccho was made to show an iconic segment of Ginza Chūō Street in the heart of Tokyo. This book depicted how the street looked post-WW2 (the photographs were taken in 1953) with notations on the street’s buildings before the 1923 Kanto earthquake, post-earthquake, and before WW2.

In 1966, Ed Ruscha created a remarkably similar accordion book, Every Building on the Sunset Strip. Ruscha shows this iconic Hollywood street as topographical and conceptual. The book was printed cheaply and priced affordably; intentional so in order to offer an affordable way for anyone to experience/own this culmination of the American Dream.

In 2018, cars owned by the multinational technology company Google crisscross the globe, photographing everything in their path to create their Street View feature, allowing a viewer to see the margins of roadsides around the world. You can see every building on Sunset Strip or Ginza Chu Street, for example. But you can also visit the peripheries. To make this triptych, I visited Skid Row and isolated every makeshift home/structure that I could find there.

Cherry Bombs, 2018.

After seven years in DC, I finally made it to see the cherry blossoms around the reflecting pool. This is a map of images of every cherry tree around the reflecting pool.

One Mile Panorama in North Dakota, 2018.

VII-Drawing

Evening Sky with Straight Rainbows, 2018.

Making Mountains, 2018.

In 2007, I drove down this road in Coastal Texas and it was the flattest landscape I’d ever seen. So, when chance brought me back to this road again in 2018, I took a photo, and decided to make mountains on the horizon of this impossibly flat landscape.

Reversed Landscape: Waterfall Meets Tree in the Jungle, 2017.

This is a photograph of a tree and a waterfall coming together in a lush green ravine. But since the landscape is upside-down, backwards, and a negative, you might not recognize it right away.

Global Roasting, 2013.

Imaging living on a planet with five suns… Consider the path that that plant might follow: It’d be a wonky, bumpy, and irregular orbit, traveling around the center of the system’s mass. Every once-in-a-while, the suns might line up, and you could see them all rise or set in unison. Or three rising while two sets. Simultaneous sunrise and sunset. Imagine the beauty of that! The planet might be considerably hotter than ours, but maybe not. Certainly the seasons would be complicated. But if you lived on that planet, you'd adapt. It would become utterly ordinary. There'd be overpasses and parking lots, and there’d even be street lights, just in case none of the suns were up in the sky.

Drawing Towards Significant Change

These images are my photographic sketches. I think of many of these works are failures. But important failures. Works that I needed to get somewhere else or are my best attempt thus far at getting somewhere that I want to go, and so I cherish them.

Failure is a rarely celebrated part of progress and innovation in the arts and the sciences (as well as everything in between). With an artistic practice where each image I make is often radically different than the previous work, failure is especially inevitable and also especially generative. So here I am, celebrating my failures and my jokes, and putting them up here for you to puzzle over, laugh at or reflect on.

I certainly think of my failed images more often than I think of the successes. They’re like itches that I can’t help scratching: what is it that I liked about this idea and where did I go wrong? Is the problem technical or conceptual? Or just that I didn’t do enough, and I somehow feel guilty about that? So I will keep plugging away at the idea until I’m satisfied.

In the sciences, where things are a bit more regimented than here in the arts, they have a whole process to deal with their moments of inspiration. Question. Research. Hypothesis. Experimentation. Analysis. Publish. However, when the hypothesis doesn’t work, we rarely hear about it. Such failures just don’t get published in the limited space of scientific journals.

I often think about all the redundant Master’s theses have been completed because of this limited room to value and share these failures. Knowing why and how we fail is central to innovation, and so this is why I’ve put these up for anyone to see. Maybe you’ve failed in the same way I’ve failed. Or maybe you can succeed where I’ve failed. I hope so.